Can you score 7/7?

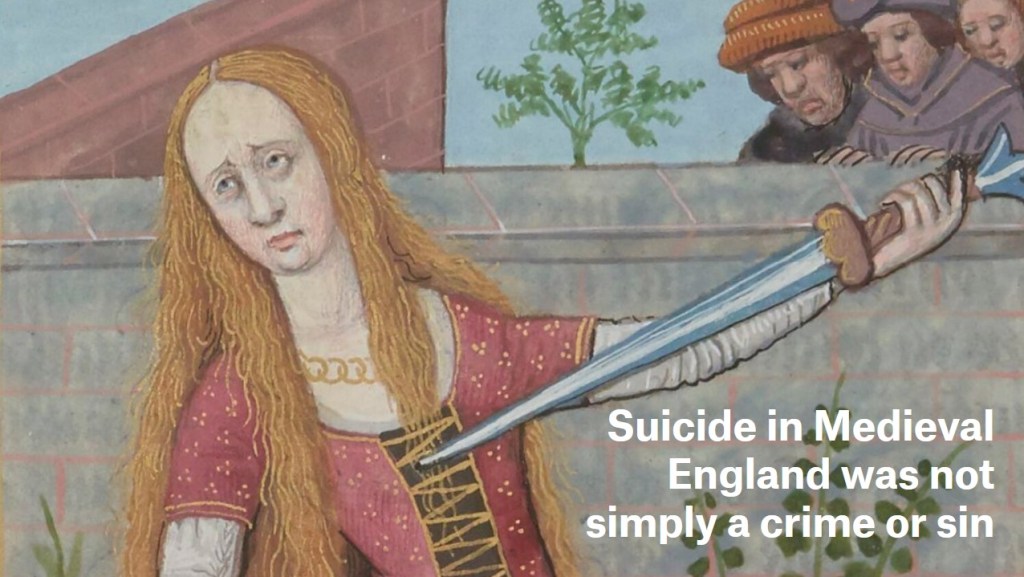

People in medieval England struggled with suicide just like people do today, and they also imagined and enacted practices of care and compassion to support the vulnerable. In the last decades of the 13th century, King Edward I extended compassionate action to a number of English subjects whose family members had died by suicide. A century later, a story in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales shows friends and neighbours responding with care to a woman on the verge of suicide. psyche.co

Richard III (1452–85) was the last Yorkist king of England, whose death at the battle of Bosworth in 1485 signified the end of the Wars of the Roses and marked the start of the Tudor age. Many myths persist about the last Plantagenet king, whose remains were discovered beneath a Leicester car park in 2012; three years later he was reburied in Leicester Cathedral. We share a comprehensive guide to the much maligned English king… HistoryExtra.com

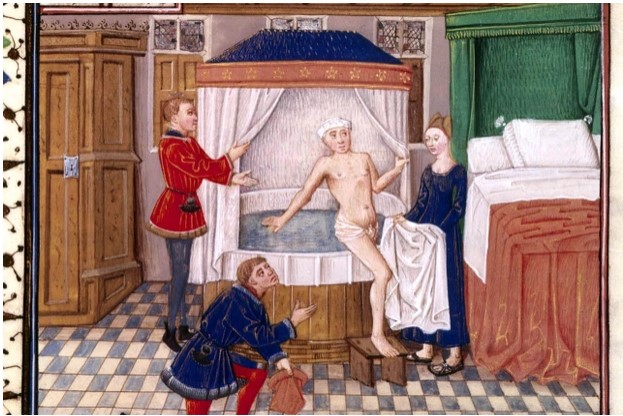

Did people in the Middle Ages take baths? Did they wash their clothes and hands – or have a general awareness of hygiene practices? If there’s one thing we think we know about our medieval ancestors, it’s that they were mud-spattered, lice-infested and smelt like rotting veg. Yet the reality appears to have been far less pungent. Here, Katherine Harvey digs the dirt on the medieval passion for cleanliness. HistoryExtra.com

Every year, in late February in England, the last hurrah before the 40 days of Lent comes in the form of pancakes.

Historically, eggs and milk that wouldn’t keep over Lent had to be used up, so pancakes became the traditional food of the day. According to lore, back in 1445, a baker had to rush to church while her frying pan was still on the stove. She had no choice but to run there, juggling the hot pan and flipping the pancake as she went. This whimsical sprint is now recreated every Shrove Tuesday across England. AtlasObscura.com

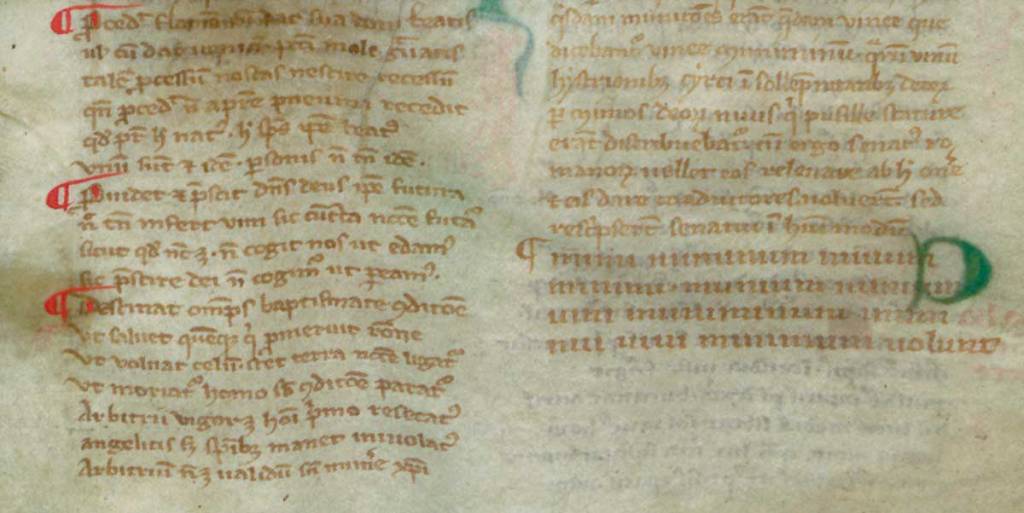

mimi numinum niuium minimi munium nimium uini muniminum imminui uiui minimum uolunt

While admittedly bizarre, this medieval Latin sentence is nevertheless perfectly comprehensible. It has been translated as:

The very short mimes of the gods of snow do not at all wish that during their lifetime the very great burden of (distributing) the wine of the walls to be lightened.

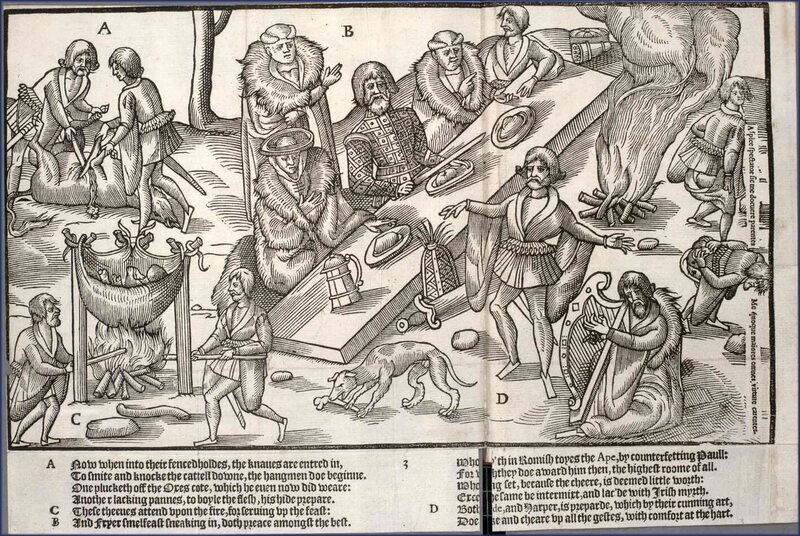

Forgery was rife in the medieval era, with some of Europe’s leading holy men cooking up reams of counterfeit documents. Levi Roach examines the fabricated texts of one Bavarian bishop to pick apart why the practice was so popular. HistoryExtra.com

Jonny Wilkes talks to Professor Emeritus Michael Hicks about how Richard III might have recovered his reputation, to some extent, and consigned the Tudors to historical obscurity.

“Richard III had a clear advantage going into the battle of Bosworth Field on 22 August 1485. As king of England, he commanded an army two or three times the size of the ragtag Lancastrian force that sailed from France, he had brought more cannon, and he was a seasoned warrior. His enemy, a Lancastrian with a tenuous claim to the throne named Henry Tudor, had never seen battle. When Richard heard of Henry’s landing, he was overjoyed: he had a chance to crush this pretender once and for all.” HistoryExtra.com

Roland, court minstrel to 12th century English king Henry II, probably had many talents.

But history has recorded only one.

Referred to variously Rowland le Sarcere, Roland le Fartere, Roland le Petour, and Roland the Farter, Roland really had a single job in the court: Every Christmas, during the court’s riotous pageant, he performed a dance that ended with “one jump, one whistle, and one fart”, executed simultaneously. AtlasObscura.com

When we picture the libraries of the Middle Ages, we see heavy tomes chained to wooden benches, far away from an accessible open space. It is a place forbidden, guarded jealously by the hooded librarian of The Name of the Rose, Malachi of Hildesheim—a domain of men. No books can leave this prison. time.com